Table of Contents

Acknowledgments…………………………………………………………………………………………………..……………………… 1

Introduction ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..…………….3

-

The History of Efforts to Set Limits on Public Defender Workloads …………………………..7

-

The 1973 National Advisory Commission Standards ….…………….…………. 7

-

Weighted Caseload Studies ………………………………………………………………………. 8

-

-

Background to ABA SCLAID’s Development of a Workload Study Methodology…..11

-

Overview of ABA SCLAID Defender Workload Studies ……………………………………….…..….14

-

The System Analysis: The “World of Is”……………………………………………………………….. 14

-

The Delphi Process: The “World of Should”………………………………………..……..………. 14

-

The Research Team………………………………………………………….…………..…..15

-

Local Support Necessary for a Successful Workload Study …… 15

-

Working as a Team …………………………………………..……………………………… 16

-

Participants………………………………………………………………………………….………16

-

CaseType/CaseTaskSelection…………………………… …………………………….17

-

The Structure of the Delphi Process……………………………….…………….. 18

-

The Report………………………………………………….……………………………………… 19

-

-

-

Lessons Learned and Open Questions………………………………………………………………………21

-

Decisions in System Analysis ……………………………………………………………………… 21

-

Timekeeping ………………………………………………………………………….…………. 22

-

The FTE and Caseload Methodology ………………………………………….. 24

-

-

Decisions in the Delphi Process ………………………………………………………………… 25

-

How Many Delphi Panels?……………………………………………………………….26

-

How Many Case Types/Case Tasks? …………………………..……………….. 27

-

Trial v. Plea Analysis ………………………………………………………………………… 28

-

Survey Interface Options ……………………………………………………………….. 28

-

Structured Feedback …………………………………………..………………………….. 31

-

Attrition…………………………………………………………………………………………………32

-

-

Timeline for a Workload Study ……………………………………………………………………. 32

-

Costs of a Workload Study……………………………………………………………………………..32

-

-

Conclusion………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..34

Acknowledgments

This report1 provides an overview of efforts to quantify, with reliable data and analytics, maximum caseloads for public defenders.2 In particular, the report details the Delphi method as utilized

by several major accounting and consulting firms, working with the American Bar Association Standing Committee on Legal Aid and Indigent Defense (ABA SCLAID), to establish jurisdiction specific workload standards for public defense providers.

This report was authored by three individuals who each worked on the ABA SCLAID workload studies: Stephen F. Hanlon, who has served as the Project Director on all of the ABA SCLAID workload studies, Malia N. Brink, who edited the Rhode Island and Colorado reports and then served as Deputy Project Director on the Indiana Study, and Norman Lefstein, who consulted on all of the ABA SCALID workload studies before his death in August 2019.

Stephen F. Hanlon founded the Community Services Team (CST) at Holland & Knight in 1989 and served as the Partner in Charge of the CST for the next 23 years. Since his retirement from Holland & Knight at the end of 2012, Mr. Hanlon has confined his practice to assisting and representing public defenders with excessive caseloads. He served as general counsel to the National Association for Public Defense and is a Professor of Practice at Saint Louis University School

of Law. Mr. Hanlon was lead counsel for the Missouri Public Defender in State ex rel. Mo. Public Defender Commission, 370 S.W.3d 592 (Mo. 2012)(en banc), which was the first state supreme court case to uphold the right of a public defense organization to refuse additional cases when confronted with excessive caseloads.

Malia N. Brink has spent over 15 years working on criminal justice reform issues with a focus on public defense reform. She currently serves as the Counsel for Indigent Defense to ABA SCLAID. Before joining the ABA, Ms. Brink served as the Public Defense Project Director at the Justice Programs Office of American University and the Director of Institutional Development and Policy Counsel at the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers. Ms. Brink also serves as a Lecturer in Law at the University of Pennsylvania Law School.

Norman Lefstein was a renowned legal scholar and academic, whose 45 years of scholarship focused on indigent defense, criminal justice, and professional responsibility. In 2011, the ABA published his book, Securing Reasonable Caseloads: Ethics and Law in Indigent Defense. In addition, he played a major role as co-reporter in writing Justice Denied: America’s Continuing Neglect of Our Constitutional Right to Counsel, published by the Constitution Project in 2009. During the 1990s, Dean Lefstein was chief counsel for the Subcommittee on Federal Death Penalty Cases, and in this capacity, he directed the preparation of Federal Death Penalty Cases: Recommendations Concerning the Cost and Quality of Defense Representation, which was approved by the Judicial Conference of the United States. Professor Lefstein served as Dean of the IU McKinney School of Law from 1988-2002. Prior to becoming the law school’s leader, Professor Lefstein was a faculty member for 12 years at the University of North Carolina School of Law in Chapel Hill. Before moving into academia, Professor Lefstein served as director of the Public Defender Service for the District of Columbia, an Assistant United States Attorney in Washington, D.C., and as a staff member of the Office of the Deputy Attorney General of the U.S. Department of Justice. Early in his career, he directed a large-scale Ford Foundation research project in which legal representation was furnished to juveniles in three metropolitan cities.

The authors must acknowledge the tremendous work of the accounting and consulting firms with which ABA SCLAID partnered in conducting the public defense workload studies: RubinBrown, Posterwaithe and Netterville, and Blum Shapiro.

Particular thanks are owed to past Chairman of RubinBrown, James Castellano, and the entire firm. In partnering on the first ABA SCLAID workload study in Missouri, RubinBrown conducted a comprehensive review of not only the use of the Delphi method, but also other potential methods, and developed a national blueprint for conducting these workload studies

The authors also wish to acknowledge the members and staff of ABA SCLAID. Without their advocacy and support, the workload studies would not have been possible. Finally, the authors wish to thank the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers (NACDL) for partnering with us on the Rhode Island Project, as well as this report. Special thanks to Bonnie Hoffman, NACDL’s Director of Public Defense Reform and Training, for editing this report.

Introduction

In Gideon v. Wainwright,3 the United States Supreme Court recognized that the Sixth Amendment right to counsel extends to state criminal proceedings and that every person who stands accused of a crime requires the guiding hand of counsel to assist in their defense. In so doing, the Court declared defense counsel for the accused essential to ensuring fairness and equality in our criminal justice system.

[I]n our adversary system of criminal justice, any person haled into court, who is too poor to hire a lawyer, cannot be assured a fair trial unless counsel is provided for him. . . That government hires lawyers to prosecute and defendants who have the money hire lawyers to defend are the strongest indications of the widespread belief that lawyers in criminal courts are necessities, not luxuries. The right of one charged with crime to counsel may not be deemed fundamental and essential to fair trials

in some countries, but it is in ours. From the very beginning, our state and national constitutions and laws have laid great emphasis on procedural and substantive safeguards designed to assure fair trials before impartial tribunals in which every defendant stands equal before the law. This noble ideal cannot be realized if the poor man charged with crime has to face his accusers without a lawyer to assist him.4

The purpose of the Sixth Amendment cannot be achieved simply by requiring that a person with a law license stand by the side of the accused individual in court. Defense attorneys must provide effective and zealous assistance of counsel pursuant to prevailing professional norms, including the rules of professional conduct.5

In the 50 years since the Gideon decision, America’s public defense providers have struggled to meet these standards. Excessive caseloads are routinely identified as a root cause of the inability In the 50 years since the Gideon decision, America’s public defense providers have struggled to meet these standards. Excessive caseloads are routinely identified as a root cause of the inability to meet standards, as detailed in the numerous national reports analyzing this crisis.7 In short, excessive caseloads stand as a core, overarching issue in public defense.8

In 2003, following the 40th anniversary of Gideon, the American Bar Association’s Standing Committee on Legal Aid and Indigent Defendants (ABA SCLAID) published a detailed report on the state of public defense9 nationally.10 The report was based on testimony submitted at a series of public hearings held around the country. It concluded that “too often . . . crushing workloads make it impossible for [public defenders] to devote sufficient time to their cases, leading to widespread breaches of professional obligations.”11 The report cited examples of excessive caseloads–often with lawyers handling more than 1,000 cases per year–in Maryland, New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and Nebraska.12

Five years later, in 2009, the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers (NACDL) published Minor Crimes, Massive Waste: The Terrible Toll of America’s Broken Misdemeanor Courts, a report looking specifically at misdemeanor courts.13 Again it documented that defenders from across the country had massive caseloads, some handling in excess of 2,000 cases per year.14 More recently, a 2016 series of articles noted Kentucky defenders averaged 448 cases in 2015 and Missouri defenders often have upwards of 150 clients at one time.15 Data from the Texas Indigent Defense Commission indicates more than 300 private attorneys each accepted over 250 assigned cases

in 2015, with a number of those attorneys accepting 500 cases or more.16 Notably, this is often in addition to the private, retained cases these attorneys also accepted during the same year.

The simple reality is that, regardless of talent and experience, a lawyer with too many clients cannot comply with their professional and ethical duties to each and every individual client

who is entrusted to them.17 For example, the Model Rules of Professional Conduct (Model Rules) require all attorneys–including public defenders18–to provide competent and diligent representation.19 Competence requires not only legal knowledge and skill, but the “thoroughness and preparation reasonably necessary for the representation.”20 An essential element of competence is “adequate preparation.”21

The ABA Defense Function Standards establish standards of practice for criminal defense lawyers.22 They include the need to investigate case facts,23 research the law,24 communicate

with clients,25 negotiate with prosecutors,26 file appropriate motions,27 and prepare for court.28 Importantly, defense attorneys must perform these tasks regardless of whether the case proceeds to trial or is resolved by a guilty plea.29 Defenders cannot do all these things for all clients when they have too many cases. By necessity, if a lawyer has too many cases, competent work for one client will result in unreasonable delays or a lack of work for other clients.30

Because excessive workloads create a grave risk of harm to clients, the Model Rules of Professional Conduct require lawyers to limit their workloads. Moreover, both ABA practice standards and Model Rules require that public defenders take steps to prevent or correct excessive workloads.31 “Continued representation in the face of excessive workloads imposes a mandatory duty to take corrective action in order to avoid furnishing legal services in violation of professional conduct rules.”32 Attorneys who face excessive workloads must withdraw from cases or refuse additional cases.33 The ABA Eight Guidelines of Public Defense Related to Excessive Workloads require that providers take corrective action in advance, “to avoid furnishing legal services in violation of professional conduct rules.”34

When an excessive caseload forces a lawyer to choose among the interests of clients, depriving some if not all of them of competent and diligent defense services, the situation also constitutes a conflict of interest.35 While the lawyer may be able to provide reasonably effective assistance of counsel and meet ethical obligations for some clients, doing so requires the lawyer to sacrifice duties owed and the provision of effective assistance to other clients. In this situation, “there is

a significant risk that the representation of one or more clients will be materially limited by the lawyer’s responsibilities to another client[.]”36

Defenders with excessive caseloads inevitably engage in triage and clients suffer real harm as

a result. For example, a prosecutor in Miami extended a time-sensitive plea offer of 364 days in

jail and seven years of probation to a public defender for a client charged with a significant felony. Because the defender had 11 cases set for trial on the same day that the prosecutor required

a response, the defender failed to convey the plea offer to the client. When she contacted the prosecutor after the deadline to accept the offer the prosecutor said the offer was no longer available. The client later pleaded guilty with a significantly less favorable agreement, receiving five years in prison plus probation.37 For this client, the cost of an overburdened public defender was an additional four years of incarceration.

Excessive caseloads also prevent defenders from reviewing and assessing case weaknesses in a timely manner. Consider the case of Donald Gamble, who was charged with two counts of robbery and initially represented by a defender with too many cases. Mr. Gamble was detained pretrial and no progress was made on his case for a year, after which his public defender resigned her position. When a Loyola law professor subsequently accepted the case, she reviewed the file and quickly identified conflicts between security footage and other evidence in the case. She presented the conflicting evidence to the judge and, a few days later, the prosecutor dropped all charges.38 For Donald Gamble, the cost of an overworked public defender was a year in jail despite clear evidence of innocence.

In 2017 current and former Orleans Parish public defenders articulated their grave concerns regarding the inevitable errors caused by excessive caseloads on an episode of the television news show 60 Minutes. Nine defenders shared that they all believed innocent clients had gone to jail because they lacked the time to properly represent their clients.39 An overburdened lawyer simply cannot meet the effectiveness standards of the Sixth Amendment right to counsel.

But how many cases are too many? For almost 45 years, the public defense community has struggled to develop reliable caseload/workload limits. Most recently, ABA SCLAID and others have utilized the Delphi methodology in seeking to provide meaningful limits for public defenders in particular jurisdictions. As of this writing, ABA SCLAID has contributed to studies completed in Colorado, Louisiana, Missouri, and Rhode Island, and consulted on a study completed in Texas.40 A workload study was attempted in Tennessee but failed for reasons that will be discussed below. An additional ABA SCLAID study was subsequently completed during the drafting of this article in Indiana.

This report will detail the methodology used in the ABA SCLAID workload studies and share lessons learned. The purpose of this report is to assist public defense organizations41 in determining whether they have the necessary infrastructure and resources to undertake similar studies, and to assist other research entities that may seek to conduct such studies. Part I of this report reviews the history of efforts to develop reliable workload limits for public defenders. Part II provides an overview of the Delphi method used by ABA SCLAID and its research partners. Part III delves deeper into the ABA SCLAID use of the Delphi method, looking at decisions made during implementation.

I. The History of Efforts to Set Limits on Public Defender Workloads

A. The 1973 National Advisory Commission Standards

In 1973, 10 years after Gideon, the National Advisory Commission on Criminal Justice Standards and Goals (NAC) endeavored to set the first public defender caseload limits (NAC Standards). The NAC adopted the recommendation of a National Legal Aid and Defender Association (NLADA) committee which stated that individual defenders’ annual caseloads should not exceed 150 felonies, 400 misdemeanors (excluding traffic cases), 200 juvenile cases, 200 mental health cases, or 25 appeals, or a proportional combination thereof.42 The NAC Standards were considered the national caseload standards for many years.

In 2002, the ABA promulgated its Ten Principles of a Public Defense Delivery System.43 Principle 5 of that document directs that a lawyer’s workload be “controlled to permit the rendering of quality representation.”44 The Commentary to the Principle states “[n]ational caseload

standards should in no event be exceeded” and cites to the NAC Standards as an example

of such national standards.45

In 2007, NLADA’s American Council of Chief Defenders (ACCD) adopted a resolution recommending “public defender and assigned counsel caseloads not exceed the NAC recommended levels.”46 An accompanying memorandum observed that while the NAC Standards “have proved resilient,” the NAC levels must be altered to account for myriad local practices, including insufficient support staff levels, complex or severe sentencing schemes, particularly complex cases, and the need to advise clients regarding collateral consequences.47

The exceptions and need for alterations noted in the ACCD’s resolution and accompanying memorandum highlight the limited usefulness of the NAC Standards. Because the Standards group cases together in very broad classifications (e.g., felony, misdemeanor, juvenile), they do not allow for consideration of the variation among case categories. For example, the “felony” classification encompasses everything from theft and drug possession to rape and murder. Additionally, other common case types, such as probation violations, are not listed at all. For this reason, the ACCD recommended “that each jurisdiction develop caseload standards for practice areas that have expanded or emerged since 1973 and for ones that develop because of new legislation.”48 One suggestion from the ACCD was to develop adjustments or case weights to address how different factors impact or alter the appropriate caseload standard in a particular jurisdiction.49

The Missouri State Auditor raised similar concerns and rejected the use of the NAC Standards in an October 2012 report. The Auditor was asked to review the Missouri Public Defender’s caseload crisis protocol, under which the public defender’s office sought to refuse cases when the caseloads were too high. In the protocol, the refusal limit was based substantially on the NAC Standards,

with adjustments made for things like complexity through a case-weighting scheme similar to what was recommended in the ACCD opinion.50 In rejecting the protocol, the Auditor noted that there was “very little information regarding the methodology and factors considered in the development of the [NAC S]tandards.”51 He further noted, as the ACCD had, that the NAC Standards “did not distinguish between types of felony offenses and were not established for certain types of cases.”52 The Auditor concluded that “[w]ithout adequate information to support how the national caseload standards were derived or maintaining documentation to support assumptions and decisions regarding case weights, the [Missouri State Public Defender] is unable to demonstrate it has accurately converted the standards to case weights.”53

B. Weighted Caseload Studies

Researchers have also explored weighted caseload studies as a way to set appropriate caseload limits. Like the ACCD recommendation, these studies establish case weights and adjustments from a norm, but instead of the norm being the NAC Standards, the norm was often the current caseload in the jurisdiction. Many public defense weighted caseload studies were conducted between

1995 and 2010 by the Spangenberg Group.54 The National Center for State Courts (NCSC)55 also conducted three statewide weighted caseload studies: Maryland (2005),56 New Mexico (2007),57 and Virginia (2010).58 RAND recently completed a statewide workload study in Michigan (2019).59 The federal defender system has also used a variation of case weighting to address caseloads.60

A review of the NCSC New Mexico workload study demonstrates how these studies typically

work. First, groups of public defenders and private contract lawyers met to determine relevant workload factors and tasks associated with effective representation in each type of case. For New Mexico, 11 different types of cases were chosen for the study.61 Second, the NCSC trained the participating lawyers on how to properly track and record time using a web-based program, and had attorneys record the time spent on both case-related and non-case related activities for a six- week period.62 The NCSC opined that this short period of time, given the high level of participation, was sufficient to produce “a valid and reliable snapshot from which to develop case weights.”63 The NCSC concluded from that data that attorneys were spending, for example, almost seven hours on each non-violent felony case64 and called this a “preliminary case weight.” The “case weight” data collected and documented what the attorneys were currently doing on cases operating under the caseload and time constraints they were currently experiencing. This represented current practice or the measure of the world of “what is.”

To move from that world of “what is”–which does not necessarily capture the time necessary to perform essential tasks effectively–to the world of “what should be,” the NCSC used a “quality adjustment process,” which consisted of two parts. First, a web-based “sufficiency of time survey” was sent to the attorneys asking whether they had sufficient time to perform key tasks of effective representation.65 Then, after data was gathered, veteran public defenders from offices across the state were convened to consider the results from the time study and various areas of concern identified by the sufficiency of time survey. In New Mexico, these attorney groups reviewed 90 distinct events related to attorney performance. Of these 90 decision points, quality adjustments were made to 21.66 In each instance in which a quality adjustment was made, the group was asked to provide a rationale and justify any increase in attorney time.”67

“The combination of the case-related time study data (representing current practices, or ‘what is’) and the quality adjustment data (representing preferred practices, or ‘what should be’) creates a [final] ’case weight’ for each case-type category.”68 The NCSC staff then determined the number

of days per year (233 days) and hours per day (6.25 hours) attorneys had to perform case-related activities. Applying these case weights to the time allotted, the NCSC then produced annualized caseload limits. At the conclusion of this process, the quality adjusted caseloads in New Mexico came out very close to the NAC Standards, with slightly fewer felonies allowed: 144 felonies (or 138 felonies, including murder), rather than the 150 in the NAC Standards, and more misdemeanors (414 in comparison to the NAC’s standard of 400) and juvenile cases (251 in comparison to the NAC standard of 200).69

Applying the case weights to the projected caseload of the public defender and dividing them

by the hours that an attorney has for case work, the NCSC was also able to produce a full-time employee equivalence staffing number.70 Based on those calculations, the NCSC study determined that the New Mexico Public Defender program needed 41 additional attorneys, an increase from 169 to 210.71

In summary, weighted caseload studies start with the actual time spent, as calculated during a time study. This time study is the basis for all other calculations. An attorney survey determines whether they believe this is sufficient time to complete the tasks. Thereafter a smaller, more experienced group of public defenders reviews the time allotment and based on the survey results and personal experience, determines whether additional time should be added to “perform essential tasks and functions effectively.”72

While weighted caseload studies provide critical insights into how to conduct a more structured inquiry into public defender caseloads, ABA SCLAID and its partners found certain aspects of the weighted caseload studies problematic. First, the length of time studied often is insufficient. The NCSC New Mexico study, for example, used six weeks of time data, which is not long enough to cover even low-level cases from opening to close. Extrapolations made from such a limited sample are prone to error. Second, beginning consideration with current time expenditures as the basis

for any of the calculations reinforces existing systemic deficiencies.73 Third, the time adjustment process was not tied to particular standards; instead, attorneys surveyed were simply asked to

use their experience to determine whether they generally had enough time for a particular task. Similarly, the small group of experienced public defenders asked to evaluate the need for time adjustments operated without reference to standards. In this process, “individual lawyers might be reluctant to admit that they should have spent more time on their cases, regardless of whether the data was submitted anonymously. There is also some risk that defenders might not appreciate that they should have spent more time on their cases, simply because they have not done so in the past and believe what they have been doing is perfectly fine.”74

II. Background to ABA SCLAID’s Development of a Workload Study Methodology

A series of events in 2011 and 2012 drove ABA SCLAID to consider an alternative method

for examining defender workloads. In 2011, the ABA published Norman Lefstein’s Securing Reasonable Caseloads: Ethics and Law in Public Defense, which detailed the various efforts undertaken thus far and the difficulties with each of those efforts. In that same year, proceedings also began in the Missouri case State v. Waters.75

In Waters, relying upon the Missouri Public Defender’s protocol for providing a certification of unavailability once a district defender’s office exceeded the established caseload maximums, an office moved to be relieved of further representation of clients due to excessive caseloads. The office also cited to the obligations the attorneys bore under the applicable Rules of Professional Conduct and the obligation to provide effective assistance of counsel under the Sixth Amendment. Although the trial judge conceded that the public defenders’ caseloads were excessive, the court nevertheless ordered the office to continue representing new eligible defendants.76

On appeal, the Missouri Supreme Court found that the trial court exceeded its authority by appointing the public defender to represent a defendant in contravention of the Rules of Professional Conduct, the Sixth Amendment, and the Missouri Public Defender’s caseload maximum rule, and ordered the trial court to vacate its order.77 Thus, Waters stands for the proposition that when a public defender office can demonstrate that it has so many cases that

its lawyers cannot provide competent and effective representation to all their clients, lawyers may–indeed, must–refuse additional appointments and judges may not appoint them to represent additional defendants.

Although Waters was decided on July 31, 2012, in October 2012, as noted above, the Missouri State Auditor found the Missouri Public Defender’s caseload crisis protocol in invalid because it was based substantially on the NAC Standards, which lacked sufficient support. As a result, the promise of Waters and its mechanism for declining cases was dependent on finding a more reliable way to measure whether a public defense provider has too many cases.

In the immediate aftermath of the Waters decision and Missouri State Auditor’s report, Stephen F. Hanlon, who was lead counsel for the Missouri State Public Defender (MSPD) in Waters,

was retained by MSPD to find a reliable alternative to using the NAC Standards to enforce the Waters decision. Mr. Hanlon investigated methodological options, including the recommendation made by Professor Norman Lefstein in Securing Reasonable Caseloads to consider utilizing the Delphi method. Mr. Hanlon then conducted an extensive literature review of the Delphi method, preliminarily concluding it could have merit to apply to the problem of reliably determining appropriate defender caseloads. He then began to develop a potential plan for a Delphi-based public defender workload study.

Realizing that additional expert assistance would be required to design and conduct a workload study, Mr. Hanlon began a search for an accounting firm that could complete the requisite research, design and conduct a workload study in Missouri. He identified RubinBrown, one of the nation’s leading accounting and consulting firms. He submitted the results of his literature review and his initial design work to RubinBrown and proposed to ABA SCLAID that it retain the accounting firm RubinBrown to:

-

Conduct a thorough literature review of previous public defender workload studies and the Delphi method;

-

Determine whether the Delphi method was a reliable research method capable of generating a reliable consensus of expert opinion for a workload study for the Missouri Public Defender or determine an appropriate research method for setting appropriate workload for a public defender office; and

-

Conduct a reliable workload study of the Missouri Public Defender system that would have, as its basis, ABA practice standards and the Rules of Professional Conduct.

After an exhaustive literature review, RubinBrown concluded that the Delphi method was a reliable research tool to determine the appropriate workload for a public defender office because it was capable of generating a reliable consensus of expert opinion. As Professor Lefstein had observed:

The Delphi method is based on a structured process for collecting and distilling knowledge from a group of experts by means of a series of questionnaires interspersed with controlled opinion feedback. Delphi is used to support judgmental or heuristic decision-making, or, more colloquially, creative or informed decision- making. The technique is recommended when a problem does not lend itself to precise measurement and can benefit from collective judgments, which is precisely the situation when a defense program considers how much additional time its lawyers need to spend on a whole range of activities involving different kinds of cases.78

RubinBrown noted that the Delphi method, developed by researchers at the Rand Corporation over 60 years ago, “has been employed across a diverse array of industries, such as health care, education, information systems, transportation, and engineering.”79 “The purpose of its use beyond forecasting has ranged from ‘program planning, needs assessment, policy determination, and resource utilization.’”80 The ABA SCLAID public defender workload studies are, in many ways, program planning and needs assessment studies. Respecting the accuracy of opinions reached by Delphi panelists, RubinBrown observed that “researchers have found that the majority of studies provide compelling evidence in support of the Delphi method” as compared to “unstructured interacting groups.”81

Thereafter, Mr. Hanlon, ABA SCLAID and RubinBrown outlined the following essential features of a public defense workload study:

• The professionals conducting the workload study must be the facilitators of the study, not the arbiters of what is “appropriate”. The governing principle with respect to the professional judgment of the Delphi panel must be “[l]et the chips fall where they may.”

The professional judgments must come from both public defenders82 and private practice criminal defense lawyers.

-

A successful workload study requires two areas of expertise: (1) surveying and data analysis, and (2) law and standards.

-

Legal, practice and ethical standards, not the results of any timekeeping data, are the appropriate anchors83 for the professional judgments in the study.

• In this standards-based inquiry, the standards that drive the study are the ABA Criminal Justice Standards,84 the applicable Rules of Professional Conduct,85 and the United States Supreme Court’s holding in Strickland v. Washington that an indigent criminal defendant is entitled to “reasonably effective assistance of counsel under prevailing professional norms.”86

• In particular, the instructions to the adult criminal Delphi panel, which serve much the same function as jury instructions, would emphasize ABA Defense Function Standard 4-6.1(b): “In every criminal matter, defense counsel should consider the individual circumstances of the case and of the client, and should not recommend to a client acceptance of a disposition offer unless and until appropriate investigation and study of the matter has been completed. Such study should include discussion with the client and an analysis of relevant law, the prosecution’s evidence, and potential dispositions and relevant collateral consequences. Defense counsel should advise against a guilty plea at the first appearance, unless, after discussion with the client, a speedy disposition is clearly in the client’s best interest.”87

• Timekeeping data should not be used as an anchor for the professional judgment of the Delphi panel to avoid institutionalizing current practices, which may be deficient.

Following these basic principles, ABA SCLAID began its work in Missouri in early 2013.

III. Overview of ABA SCLAID Defender Workload Studies

ABA SCLAID’s application of the Delphi method to public defender workload studies requires two steps: (1) a system analysis (the “world of is”) and (2) the Delphi process (the “world of should”). The system analysis data is ultimately compared to the workload standards as determined through the Delphi method to identify potential gaps, if any, in the current system.

A. The System Analysis: The “World of Is”

The system analysis is an examination of the current and historical workload of the public defense system under study. The system analysis should include staffing numbers and caseloads for public defense attorneys going back, if possible, at least three years.88 If the data cannot be gathered directly from the public defense organization, it may be available from the courts or other relevant agencies.

In states where the public defense organization has comprehensive oversight authority over all public defense providers and where all providers use case management systems that collect core data on caseloads, most of the data is relatively easy to collect. In states with less centralized systems, where public defense providers have little statewide oversight, use different case management systems with different data entry criteria, or use a large number of contractors or part- time public defense providers and do not gather information on their non-public defense caseloads, the data can be significantly harder to collect.

Additionally, to be most effective, this system analysis should include timekeeping data to show how current public defense attorneys are expending their time.89 Timekeeping data tracks time spent

on specific tasks and the particular type of case for which the task is being done. Timekeeping

data allows for a more robust understanding of the time public defense providers in the jurisdiction currently spend on case specific work, and the time currently spend on other job requirements, such as administrative tasks, travel time, training, and supervision, which are not captured in the Delphi process. Timekeeping also allows for more granular comparisons between historical time expenditures and the time recommendations that result from the Delphi process.

Issues that arise during the System Analysis and how they were addressed during ABA SCLAID workload studies are discussed in detail in Section IV(A), below.

B. The Delphi Process: The “World of Should”

In ABA SCLAID workload studies, the Delphi process is utilized to determine the amount of

time attorneys should spend on given cases. To measure this, the Delphi process leverages the expertise of participants–here criminal defense practitioners in the relevant jurisdiction–to arrive at a consensus on the two key decisions: (1) the amount of time attorneys should expect to spend on average on a given Case Task for a typical case of the particular Case Type to provide competent representation and deliver reasonably effective assistance of counsel under prevailing professional norms (Time), and (2) in what percentage cases of this Case Type should the particular Case Task be performed (Frequency).90

1. The Research Team

As noted above, a Delphi workload study is a two skill set project: one part law and standards, and one part surveying/data analysis. In the ABA SCLAID workload studies, ABA SCLAID

is responsible for the law and standards applicable to the project, and the accounting and consulting firm (consulting firm or consultants) is responsible for the empirical research and data analysis. Together, these two groups form the research team. The public defense organization being evaluated also plays a critical role, particularly in helping to identify potential participants, encouraging participation and answering questions with regard to practice in the jurisdiction.

RubinBrown served as the consulting firm on the first ABA SCLAID workload study, The Missouri Project, and they were instrumental in developing the blueprint on which subsequent studies have been based. The most important roles of the consulting firm are to design the surveying tool, conduct the requisite data analysis, and conduct the system analysis. Accordingly, the selected consulting firm needs to have experience in surveying, as well as data analysis and presentation. Importantly, the firm must have experience gathering and compiling data from various governmental sources. Often these skills do not exist in a single person. The most successful consulting partnerships on the ABA SCLAID workload studies have been with firms

that have put together a team of people, including a lead consultant, a data/surveying expert, and a meeting facilitator.

The ABA SCLAID portion of the research team is responsible for the law and standards applicable to the study. In the workload studies completed to date, the key standards referenced have been the ABA Criminal Justice Standards91 and the jurisdiction’s Rules of Professional Conduct. The ABA SCLAID team for these projects has consisted of Stephen F. Hanlon and Norman Lefstein, assisted by ABA SCLAID staff. Mr. Hanlon and Professor Lefstein have long records as experts in standards and rules of professional responsibility relevant to these studies. The ABA SCLAID staff person for the most recent studies, Malia Brink, is also an attorney and expert in the area of public defense. Her role is to serve as the day-to-day point person on the project, maintaining the timeline and ensuring coordination between and among the different members of the research team. Other institutions and organizations undertaking a workload study should endeavor to include on their law and standards group, individuals with substantial expertise in both the practice and ethical standards applicable to criminal defense attorneys in the study jurisdiction.

2. Local Support Necessary for a Successful Workload Study

While the public defense organization is not part of the research team, the cooperation and support of the organization is critical to the project’s success. The organization must provide expertise on the operations, personnel, and eccentricities of the criminal justice system in the jurisdiction. The research team must ensure that the public defense organization fully understands the research steps so that it can help identify potential problem areas. For this reason, the public defense organization participating in the project must have strong leadership and a demonstrable commitment to the goals of the study–to identify appropriate workloads and ensure that public defenders are limited to such workloads.

The public defense organization plays an integral role in the selection of the study participants.

If the panel participants are not appropriately expert in the areas covered by the Delphi process (e.g., if defense attorneys with knowledge of homicide cases are not included on a Delphi Panel that is tasked with developing standards for homicide cases among other adult criminal matters), the process will fail. Additionally, the public defense organization must either provide data for comparative analysis (timekeeping and/or historical staffing and caseloads) or help the research team identify available data sources and avenues for data collection. For example, caseload data may need to be collected directly from the courts and the public defense organization may serve a critical role in helping craft and facilitate the data request.

3. Working as a Team

Maintaining regular communication between and among the two parts of the research team, as well as with the public defense organization, has proved critical to the success of a workload

study. While each group has a distinct role to play, it is important that they discuss issues as they arise to ensure that a decision made by one group is not problematic for another. Imagine that the public defense organization was having trouble identifying qualified participants and decided that they should ask retired lawyers or lawyers who previously practiced in the jurisdiction, but have moved out of state, to participate. This decision is something that should be discussed by the entire research team because, for example, the data analysis consultants may find recent experience important and want to only include individuals who have practiced in the jurisdiction during the

last three years. Similarly, if a court process changes during the data collection phase, how the new process will be recorded in timekeeping should be discussed with the entire research team to ensure that timekeeping data will still map well to the information obtained from the Delphi portion of the study.

Once issues are discussed among the groups and possible consequences identified, the decision must be left to the appropriate group. For example, the entire group might discuss what data to include on the Round 2 survey and how best to present the data to participants. The ultimate decision on this point would be made by the data analysis consultants, as this falls within their sphere of responsibility. Similarly, the group might discuss how much detail to provide regarding the applicable standards in a survey instrument to not overwhelm participants. The ultimate decision on this point would be made by the members of the team tasked with law and standards. Workload studies function best when the entire group communicates well and trusts each other to make appropriate decisions in their respective areas.

4. Participants

There are three groups of participants in an ABA SCALID workload study, a Consulting Panel, which provides information on practice in the jurisdiction critical to the design of the survey instrument, a Delphi Panel, which is the list of participants in the study, and a Selection Panel, which reviews and approves the final list of Delphi Panel participants.

An ABA SCLAID Workload Study begins with the convening of a Consulting Panel, which is a group of five to 10 highly experienced lawyers who assist the research team in understanding the local practice, which is critical to survey design. Although small, the Consulting Panel should be a diverse group consisting of public defenders92 and private defense attorneys from the jurisdiction who handle the types of cases to be studied. These individuals are usually identified with the assistance of the public defense organization. The purpose of the Consulting Panel is to identify the “Case Types” and “Case Tasks” to be studied.

The attorneys who participate in the study–taking the survey, etc.–are called the Delphi Panel. Initially identified with the assistance of the public defense organization and the members of

the Consulting Panel, the Delphi Panel is made up of local attorneys with significant defense experience in the particular area to be studied (e.g., appeals, juvenile, or adult criminal cases).93 The Delphi Panel should include a mix of all types of defense practitioners (e.g., institutional defenders, contract defenders, and private practitioners ) utilized in that jurisdiction. Efforts should be made to assure that the Delphi Panel reflects the diversity of defense practitioners in the jurisdiction, including geographic, gender, racial, and ethnic diversity. The initial list of potential members of the Delphi Panel should include as many qualified lawyers in the jurisdiction as possible. Once the list of qualified Delphi panelists is compiled, a Selection Panel reviews it.

The Selection Panel, is made up reputable individuals in the jurisdiction who have extensive practical experience in the area of law to be covered in the workload study, in other words lawyers whose credentials would be universally regarded as expert, and who have extensive knowledge

of the members of the bar practicing in this are in the jurisdiction. They may be judges, law school deans, or well-respected defense attorneys. In the ABA SCLAID studies, the Selection Panel usually has been made up of three to five such individuals, which was a manageable group, but also sufficient to include representation from across the study jurisdiction. The Selection Panel members are each provided a list of proposed Delphi Panel participants. They can either meet, in person or by phone, or review the list separately without meeting. Each Selection Panel member may strike any name from that list if he or she (1) has actual knowledge of the individual and

(2) does not believe the person has the expertise or experience necessary to participate. Each Selection Panel member may also add qualified individuals to the list. Once the Selection Panelists’ strikes and additions are incorporated, the list of participants (the Delphi Panel) is finalized.

5. Case Type/Case Task Selection

The first step in developing the survey tool used in the Delphi process is to establish the relevant Case Types and Cases Tasks that will be surveyed.

Case Type is a way to group offenses of roughly similar complexity. Examples of Case Types include: murder/homicide, sex felonies, juvenile delinquency cases, and probation violations. While it is understood that, within a Case Type, case complexity can vary greatly, these groupings help create overall categories of cases that share similar complexity and types of tasks that are performed during representation.

Case Task is a way to group common tasks performed by an attorney. Examples of Case Tasks include: client communication, discovery, attorney investigation, and motions/other writing.

In the ABA SCLAID studies, the Case Types and Cases Tasks are developed by the Consulting Panel during an in-person meeting with the research team. At this meeting, the Consulting Panel is asked to break down their practice area(s) into Case Types that they would naturally group together. They usually develop a list of approximately eight to 10 Case Types. For a process addressing adult criminal cases, for example, it is common for Consulting Panels to break felony cases into low-level felonies, mid-level felonies, high-level felonies, and murder cases. In some studies, Consulting Panels also have separated out drug cases or sex crime cases as distinct Case Types.

The Consulting Panels then break down their work into Case Tasks. These Case Tasks must fairly encompass all of the work that they should perform as defense attorneys. As noted above, common Case Tasks include communication with clients, discovery, court time, motions /other writing. The Consulting Panel must then define these Case Tasks to ensure that there is minimal overlap so that it is clear where time spent on different common tasks would be allocated.

The proper identification of Case Types and Case Tasks is crucial, as it will form the basis for the subsequent determination of the workload standards (e.g., the number of minutes or hours it should take an attorney to conduct legal research in a sexual assault felony case).

6. The Structure of the Delphi Process

In ABA SCLAID workload studies, the Delphi process is an iterative study of the time and frequency associated with Case Tasks for each of the identified Case Types. In other words, the process is repeated several times with the results of each round of the process informing and shaping the next round. In the ABA SCLAID studies, the Delphi process consists of three rounds – Rounds 1 and 2 are conducted via online surveys, while Round 3 is conducted as an in-person meeting.

As structured for ABA SCLAID workload studies, the online surveys in Round 1 and 2 begin with an explanation of the standards and ethical rules applicable to the study. This overview orients

the participants to the prevailing professional norms on what constitutes reasonably effective assistance of counsel and makes clear that these standards should anchor their responses. The Delphi panelists are then asked if they have the requisite experience to respond to questions about each Case Type. For each Case Type for which they have the requisite experience, the survey then asks the Delphi panelists to provide an estimate of the amount of time an attorney should spend on a given Case Task (time), and the percentage of cases in which the Case Task should be performed (frequency). For example, a participant will be asked within the context of an identified Case Type (e.g., felony sexual assault cases) to estimate (1) the amount of time that an attorney handling such a case should spend on motions practice and (2) the percentage of felony sexual assault cases in which an attorney should conduct motions practice.

In each of the online survey rounds (Round 1 and 2), the Delphi Panel participants are instructed to complete the survey without consulting any other participant or member of the defense community. All survey distribution, collection, and analyses are completed by the consultant. Once the results are received from Round 1, the Delphi Panel’s responses are trimmed and summarized, and these trimmed summaries are presented to the panelists in the Round 2 survey (structured feedback).94

Round 3 of the Delphi process is conducted as an in-person meeting of participants. At this meeting the panel is provided trimmed summary data from the Round 2 survey (structured feedback). This meeting is facilitated by the consultants and attended by the ABA SCLAID team, who orient the panel members to the applicable law, standards and ethical rules that anchor the study. The panel members then discuss each question and come to consensus on the appropriate Case Type/Case Task time and frequency. Members of the research team do not have any input into these decisions.

It should be noted that to participate in each successive Round, the participant must complete each prior Round. In other words, Delphi panel participants who do not complete the Round 1 survey

are not invited to participate in the Round 2 survey. Participants who do not complete the Round 2 survey are not invited to participate in the Round 3 meeting.

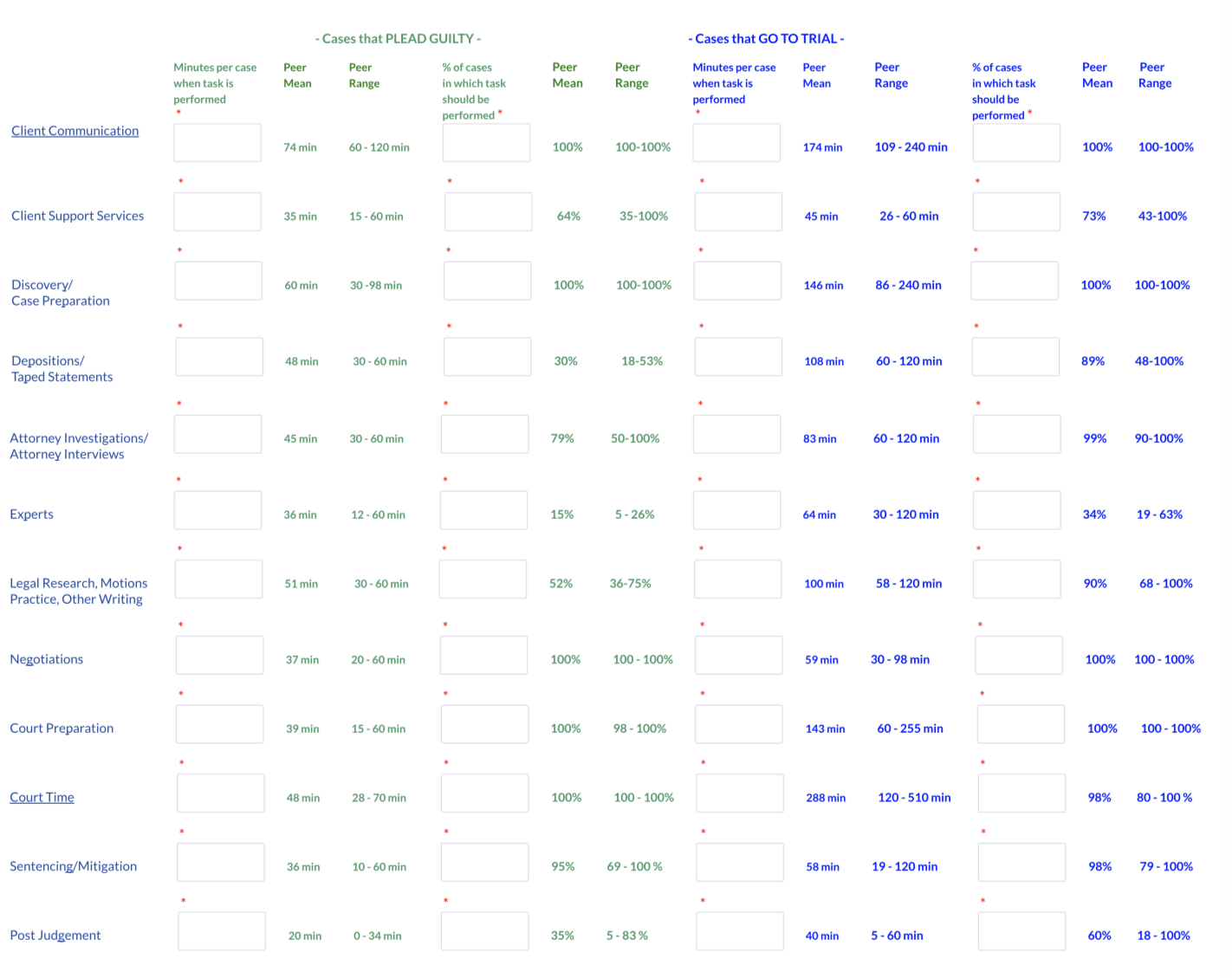

The group’s consensus decisions made in Round 3 are then used to calculate the results of the workload study. The consultants calculate the time needed by Case Type by multiplying the case time by the case frequency number for each Case Task, and then adding up the resulting time for all Case Tasks for each Case Type. This calculation is the amount of time needed for a typical case of the Case Type, which can be used to calculate overall workload standards.95 Examples of this from ABA SCALID workload studies include:

Importantly, as noted above, in ABA SCLAID workload studies, the Delphi Panel is never shown the results of the actual timekeeping or other historical data. A professional judgment was made by RubinBrown during the first workload study that the Delphi Panel’s task is to determine the “World of Should,” not the “World of Is.” There is no nexus between the two worlds. The data analysis consultants on each ABA SCLAID workload study since the Missouri report have agreed with this judgment.96

7. The Report

Once both the system analysis and the Delphi process have been completed, the research team collaborates to produce a report that contains an explanation of the study’s methods and results, including the resulting workload standards, statistics, and conclusions. To date, ABA SCLAID, together with different consultants, has completed workload studies in Missouri,97 Louisiana,98 Colorado,99 and Rhode Island.100 RAND, in conducting a review of recent public defender workload studies in preparation for its efforts to conduct a study in Michigan, included all four of the ABA SCLAID studies among those that “provided well-tested models” for conducting a public defender workload study.101 During the drafting of this report, an additional study was completed in Indiana.102

IV. Lessons Learned and Open Questions

This section reviews and explains some of the more nuanced decisions made by the research teams in applying the Delphi method over the course of completing ABA SCLAID public defense workload studies. The review focuses on key decision points in the process and the results of those decisions.

A. Decisions in System Analysis

A number of complicated issues arise when completing the system analysis for a workload study. As noted above, the system analysis is intended to provide an accurate picture of public defense as it exists in present conditions–the “World of Is.” When measured against the results of the Delphi process, it allows for a determination of whether deficiencies exist and the extent of those deficiencies, i.e., how much more attorney time (and potentially additional attorneys) would be needed to lower caseloads to the point necessary to provide reasonably effective assistance of counsel pursuant to prevailing professional norms. Addressing issues in system analysis and successfully obtaining accurate comparison data is critical because without it, while the public defense organization may know what it should do, it will not know what additional resources may be needed to achieve this goal.103

The most challenging aspect of the system analysis is gathering data from multiple sources

and determining how to combine that data for analysis. Generally, public defense is provided in three ways: institutional public defenders, who are usually full-time salaried employees; contract defenders who take a fixed number or percentage of the public defense cases in a jurisdiction

for a fixed fee or hourly rate; and attorneys who are assigned individual cases and paid on an hourly or per case basis. Public defense in any given jurisdiction often is provided by multiple organizations and even multiple systems. Typically, there is a primary system (e.g., a full-time public defender office) and a secondary system for conflicts and overflow cases (e.g., an assigned counsel system). In some jurisdictions, public defense is organized statewide and in others it is organized at the county level. With regard to the system analysis, the use of varied systems can pose challenges. Each provider or system may keep records differently and those records may be difficult to combine.

Even when a state operates a statewide public defense system with primary reliance on institutional public defender offices, there can be variations among offices that can impede data integration efforts. In Tennessee, for example, there is a process whereby a defendant in a felony case is arraigned in one court and then, if it not resolved at arraignment, transferred to another court.

In one public defender office, this was counted as a single case and tracked across the transfer from one court to another. In another office, however, it was counted as two cases. This and other inconsistencies in data gathering made it difficult to compute reliable historical caseloads in that state.

In each jurisdiction, the research team must work together early in the study process to develop a comprehensive understanding of the following: (1) the existing public defense system in the study jurisdiction; (2) what records and data exist; and (3) who controls the records/data identified. Using this information, the data analysis consultants must determine how best to calculate the historical caseload for the jurisdiction and the current personnel capacity of the jurisdiction. The Research Teams on the ABA SCLAID workload studies have used two ways of conducting the system analysis: timekeeping and the full-time equivalent (FTE) analysis.

1. Timekeeping

When attorney time can be captured to a high degree of consistency and quality, it remains

the best way of understanding the “World of Is,” i.e., how many public defenders are spending how much time on current cases. Timekeeping provides an unsurpassed level of detail in that, when done correctly, it tracks time not only by case (which can then be matched to Case Types chosen for the Delphi Study), but also by task (which can be matched to the Case Tasks chosen for the Delphi study). In other words, it can be used to see time deficiencies by Case Type and by Case Task. Timekeeping data is also very useful for management purposes after the Delphi study is concluded.

However, timekeeping has long been resisted in the public defense community. As a result, timekeeping with sufficient accuracy and consistency to allow for reliable comparisons has proven difficult in several jurisdictions.

Where timekeeping is undertaken, the public defense organization must either (1) already have

in place a functioning case management information system that includes a timekeeping system so that appropriate data collection can occur, or (2) put a timekeeping system in place before the study begins. Where timekeeping exists in the system, it is necessary to look carefully both at the categories of time collected and compliance rates before beginning the data collection period. It may be necessary to add categories and/or engage in retraining to help assure consistency in how tasks are recorded and to increase the rate of participation among defense attorneys. This will help maximize the usefulness of the timekeeping data for the workload study.

Instituting timekeeping for the purposes of a study can be problematic. There is often resistance, particularly among overworked public defenders who find this new administrative task itself time consuming. Resistance to timekeeping can result in resistance to the workload study itself if the study is blamed for the timekeeping changes. Moreover, it is not easy to go from never having kept time to keeping time with the kind of accuracy and consistency required for a study. Based on the experience of the four ABA SCLAID workload study research teams, if a jurisdiction is instituting timekeeping for the study, it must be put in place at least six months before the data collection period can begin. This allows the attorneys, most of whom likely have never kept time in fractions of an hour before, to be trained to enter time in case-specific categories and to ensure they enter their time accurately and consistently. This is an enormously challenging task. During this six-month period before data collection, timekeeping efforts must be monitored closely to determine whether time is being entered consistently.

a) Consistency in Timekeeping

One common problem that occurs in timekeeping is that different defense providers, or even different attorneys, record time differently. For example, if one office (or attorney) places time related to hearings on discovery motions under a time code called “Discovery” and another places it under a time code called “Court Time,” this inconsistency will cause inaccuracies. This is the type of issue that must be addressed in a training period and why, even where timekeeping is in place before a study begins, it is crucial to conduct a review of timekeeping processes and compliance before a study begins.

When timekeeping is undertaken, the public defense organization must ensure that the data measurement processes and practices for timekeeping are consistent across the system being studied. In other words, the protocols for timekeeping must be clear, and then the protocols must be followed by all of the attorneys. Training and supervision are critical to producing reliable data about actual time spent on cases. As this is a very hands-on, day-to-day activity, it must be the responsibility of the public defense organization.

b) The Timekeeping Collection Period

A timekeeping study should include a considerable period of reliable timekeeping data. During the timekeeping period, a significant number of cases will both begin and end. The longer the data collection period, the more reliable the data will be because it will capture more cases from beginning to end. Cases that begin and/or end outside the data collection period require separate analysis by the data analysis team. This analysis uses estimates and multipliers based upon prior years’ caseload data and the data gathered during the timekeeping period to draw the inferences about the time needed to complete the cases.104

For timekeeping analysis to be successful:

-

A significant percentage of the time reported (preferably above 50-60%) must be reported as case-specific time, i.e., time entries that are made in specific cases. If public defense attorneys do not get a significant percentage of their time recorded in case- specific entries, the data analysis consultants have trouble drawing legitimate inferences about the amount of time required for each Case Task in each Case Type.

-

At least 90% of total attorney time must be reported by public defense attorneys in the appropriate category. The data analysis consultants cannot make valid inferences about the entity studied (e.g., statewide, local, or regional offices) without a full understanding of how attorneys spend their time.

Periodic reviews of all time entry data (at least every 30 days) should be carried out to catch errors and omissions, and to maintain compliance rates at the needed levels.

The determination of what period of time is required to make the necessary inferences is a question for the data analysis consultants. In Missouri, the study looked at a 25-week period of timekeeping,105 and in Colorado, the timekeeping period was 16 weeks.106 Six months of timekeeping should be sufficient, but a longer period would be preferable as it would increase data reliability.

c) Conclusions on the Use of Timekeeping

As noted above, timekeeping data, even if accurate and consistent, is never shown to a Delphi panel under the ABA SCLAID research method. The use of timekeeping as the principal anchor has a high risk of institutionalizing current bad practices. Timekeeping, assuming it is accurate, will reflect current practices, but current practices may be severely deficient. This cannot be determined until after the Delphi study is complete. To suggest that actual time amounts are relevant is, in essence, to prejudge the situation for public defense attorneys in the jurisdiction. For this reason, providing actual time data is antithetical to the purpose of the Delphi workload study, which is to determine how much time a lawyer should require to conduct a particular task in a particular type of case to comply with applicable standards.

Instead, the applicable law and standards are the principal anchor for the consensus professional judgment of the Delphi Panel. The instructions to the Delphi panel regarding the law and standards as the principal anchor for their consensus of professional judgment serve much the same function as jury instructions, guiding the exercise of the professional judgment of each of the panel members.

2. The FTE and Caseload Methodology

Given the challenges of timekeeping, it was critical to develop an alternative method for completing the system analysis. This was done first in the Louisiana workload study.

The implementation of timekeeping in Louisiana proved problematic. First, as noted previously in this section, the implementation of timekeeping solely for the purposes of a workload study can be challenging.107 In the case of Louisiana, the timekeeping data showed that only 35.6% of the attorney time was recorded as related to a specific case.108 Most of the time was recorded in the broader categories of case-related or general work-related. When the data analysis consultants reviewed the case-related time entries, they determined that “71 percent (25,159 total hours) of Case Related time was spent on Delphi Case Tasks.”109 In other words, it was work that should have been recorded as case-specific but was not. Based on this finding, the data analysis consultants determined that the timekeeping data “underestimate[d] the Case Specific time spent on legal representation of clients on specific cases by public defenders during the analysis period.”110 For this reason, they determined that the timekeeping records “provided insufficient detail” to perform the requisite analysis.111

Instead, the consultants in Louisiana developed an alternative method of estimating the time spent on cases. They looked at historical personnel employment data for attorneys in the Louisiana public defender offices and converted the total attorney personnel to full-time equivalents (FTEs). The consultants then assumed that each FTE spent 2,080 hours112 annually on case work. In other words, the “FTE calculation conservatively assumes all hours are allocated to the legal representation of annual workload, without consideration for continuing education requirements, administrative tasks, vacation, etc.”113 While this method does not allow for a comparison of timekeeping at the Case Type or Case Task level, it does allow for a comparison of total attorney time available, based on FTE and caseloads, to total needed attorney time at the system level, based on the Delphi panel results and caseloads.

Multiplying the projected caseload (obtained by analysis of the recent historical caseloads in the jurisdiction) by the time needed by Case Type (as determined by the Delphi panel), produces the hours needed annually to provide reasonably effective assistance of counsel pursuant to prevailing professional norms. Dividing that number of hours by 2,080 (the estimated number of hours a single FTE works annually) produces the number of FTEs needed to provide defense services. The resulting number of FTEs can be compared to the number of FTEs currently in the system to calculate whether an attorney staffing deficit exists.

Using this methodology, the study in Louisiana concluded that “the Louisiana public defense system is currently deficient 1,406 FTE attorneys.”114 At that time, the Louisiana public defense system employed 363 FTE attorneys. The FTE methodology was also used in Rhode Island,115 with the study determining that the Rhode Island Public Defender “is currently deficient at least 87 FTE attorneys.”116 At the time of the study, the Rhode Island Public Defender employed 49 FTE attorneys.

One of the most challenging aspects of the FTE method of system analysis is trying to determine with the requisite degree of accuracy the number of FTEs historically in the public defense system. In Louisiana, this was relatively easy because the Louisiana public defense system operates statewide and has authority over personnel records.117 The data analysis consultants were able to obtain accurate historical FTE calculations using compensation reports and other reports available from the public defender.118 The same was true in Rhode Island.119 However, in other systems, determining FTEs can be more complex, particularly in systems that are organized on the county level, those making significant use of assigned counsel, and/or contracts.

It is also critical to understand that FTE analysis generally produces a conservative calculation of deficiencies because it assumes that all attorney time [2080 annual hours per FTE] is devoted to case-specific work.120

B. Decisions in the Delphi Process

As with the system analysis, several questions can arise during the Delphi process. This section explains some of the questions that have arisen in the ABA SCLAID workload studies and how the Research Teams chose to address them.

1. How Many Delphi Panels?

Initial workload studies, such as the one completed in Missouri, utilized a single Delphi panel. The panel was asked to address Case Types that covered all, or almost all, of the types of cases in which public defense attorneys provided representation, including misdemeanors, homicide/ murders, juvenile cases, appeals, and special writs.121

Using a single Delphi panel for a broad range of Case Types presents some problems. First, it

may not accurately reflect how most public defense attorneys practice. While the same attorney may represent clients in misdemeanor and felony cases, it is relatively rare that such attorneys also take appeals and writs. As a result, many participants in the Delphi panel may only be able

to answer questions regarding one Case Type, e.g., appeals. As appellate attorneys, they likely would not have the requisite experience in any other type of case to participate in those sections of the survey. Convincing such individuals to participate in a survey in which they must decline 90% of the questions as not relevant to their practice is difficult. Convincing these same attorneys to complete the process, including taking a full day to attend the Round 3 in-person meeting, is very difficult. Yet, their participation is critical to achieving accurate results regarding the one Case Type for which they have the requisite experience.

Second, research teams realized that having only one Case Type in specialist areas, such as appeals and juvenile cases, might not provide the adequate level of distinction necessary for these specialist practitioners to make accurate time estimates. For example, a juvenile defender has a difficult time thinking about a typical juvenile case when such cases range from status violations

to serious assaults and even murder. This frustration resulted in the number of Case Types increasing. For example, in the Colorado workload study, there were 18 Case Types, including three juvenile Case Types. This allowed the panel to distinguish between juvenile misdemeanors, juvenile felonies, and juvenile sex offense cases. However, with 18 Case Types, the number of questions the Delphi panel was required to address resulted in an exceptionally long survey.122 While the level of detail was desirable, the process became unwieldy. In looking at this closely, the research team observed that the Colorado Case Types and Case Tasks both included categories specific to juvenile practice. This observation, along with the success of specialty panels in Texas, led ABA SCLAID to consider using separate or different Delphi Panels and surveys for specialty practice areas, e.g., appeals and juveniles.

For each workload study jurisdiction, it is worth considering how many Delphi Panels to use. In thinking about whether separate panels would be useful, consider:

• Are there areas in which criminal defense lawyers generally operate as specialists, taking one type of case but not others?

-

Do defense lawyers with cases in juvenile court typically also practice in adult criminal court in this jurisdiction?

-

Do appellate defense lawyers also typically do trial work in this jurisdiction?

If a tendency toward specialization emerges, a separate Delphi Panel might be an appropriate way to retain a larger number of Case Types/Case Tasks without overly taxing participants.

In the Indiana workload study, the research team convened four separate Delphi panels: (1)

Adult Criminal; (2) Juvenile; (3) Appeals; and (4) Children in Need of Services/Termination of Parental Rights. Conducting multiple panels allowed the study to address more case types. The Indiana juvenile Delphi survey, for example, broke juvenile cases into six case types ranging from status cases to homicide cases. Additionally, at the in-person meeting of the juvenile Delphi panel, most respondents were able to participate in most Case Types, and therefore a greater portion of the discussion.

Dividing the panels need not exclude the participation of generalist practitioners. If a lawyer has significant experience in both adult criminal cases and juvenile cases, for example, he or she could participate in both panels. In the Indiana study, however, there were only a few participants invited to serve on multiple Delphi Panels. This suggests that the use of more specialized panels may, in fact, better reflect how public defense attorneys practice, at least in Indiana.

The question of how many Delphi panels to use is one that should be considered in each study jurisdiction. The use of more specialized Delphi panels has the potential to increase the level of detail reached in workload studies, however, additional panels require additional consulting time for survey design and data analysis, as well as additional in-person meetings, which is also likely to raise costs significantly.

2. How Many Case Types/Case Tasks?

A related issue that arises early in the survey development process is determining the appropriate number of Case Types and Case Tasks that should be identified for each Delphi panel. On the one extreme, why not simply have participants answer for each individual type of case (assault, robbery, burglary, trespass, etc.) and each task they undertake (preliminary hearings, client interviews, discovery motions, etc.)? On the other extreme, why not group all felonies together, as is done in the NAC Standards? The answers, when posed at the extremes, seem obvious. The overly detailed survey would be unmanageable, creating far too many survey questions to answer. The overly broad survey would make it difficult for the defenders to adequately envision the typical case, allowing them to answer the survey questions.

To a large extent this is a decision that must be made by the Consulting Panel, which, as noted above, is the group of experienced attorneys–public defenders and private practice criminal defense lawyers–that use their expertise in the jurisdiction to select the best groupings of Case Types and Case Tasks. The Case Types must cover, to the extent possible, the full range of public defense practice, and be grouped in a way that allows the Delphi Panel to understand and identify a typical case of this type. Similarly, the Case Tasks must group together aspects of a lawyer’s work on a case logically and with sufficient detail to cover almost all of the work done on a case, but not create so many tasks that answering about each of them becomes overly onerous. At the end of the day, the Delphi Panel must, in each survey and during the in-person meeting, go through each Case Type and determine the time for each Case Task.

When working with a Consulting Panel, it is important to emphasize these points, and to ask questions about whether the groupings they have selected allow them to conceive of a typical

case that they could keep in mind to answer survey questions. If the groupings seem overly detailed, questions should be asked about whether two Case Types are sufficiently similar to be combined. In the ABA SCLAID workload studies completed thus far, the number of Case Types has ranged from eight (Missouri) to 18 (Colorado). The Rhode Island study used 11 Case Types, while Louisiana used 10. The number of Case Tasks has ranged from 11 (Louisiana) to 19 (Missouri), with Colorado and Rhode Island each having 12.

3. Trial v. Plea Analysis

In the ABA SCLAID workload studies published at the time of this writing, the Case Types and Case Tasks had not been further divided into cases that go to trial versus cases that are resolved by plea or dismissal. Given the issues regarding the numbers of Case Types and Case Tasks, the research teams were wary of making this additional distinction, because it effectively doubles the number of decisions the Delphi panel must make. The research teams also did not want to somehow suggest that it would be appropriate to decide, at the outset of a case, whether the case should plead or go to trial.